Sojourn: From Monarch Pass to Portrait Monuments

Sojourn

Verb: (To make) a temporary stay at a place. Also, figurative.

Noun: A delay; a digression

July 25, 1969

“Stopped at Monarch Pass 10:00 am” Mom writes, adding “hope to make 300 miles today….”

Monarch Pass, Taken by my father in ‘69 - “The Continental Divide of the Americas (also known as the Great Divide, the Western Divide or simply the Continental Divide; Spanish: Divisoria continental de América, Gran Divisoria) is the principal, and largely mountainous, hydrological divide of the Americas.” Wikipedia

My sisters and I liked the curios sign. Dad liked the watershed sign.

“Rode the tram to the top,” mom records.

At 12,000 feet, my ten-year-old sister wanted to know if she could pee on the Pacific side while one of us peed on the Atlantic side. My dad said no. A bit later after we were back on the road to make our 300 miles, Dad praised her for getting the concept of water flow in relation to a divide right.

“The drive between Montrose and Durango is a scanty road. Very pretty.”

The pass separates the Uncompahgre and Las Animas River watersheds and serves as a dividing point between the Uncompahgre and San Juan National Forests.

Sometime after Red Mountain Pass, we set up camp.

It started to rain during the night “and rained till about 3 in the morning. I had to go out in the rain,” Mom notes, “to fix the [tent] window and [tent] door to keep the rain out.”

The first thing my sister said the next morning was “The water is headed for the Pacific!”

The rest of us were more interested in our damp sleeping bags.

The next day more heavy rain. One of the tent poles fell and soaked two sleeping bags. We needed a clothes dryer and found a laundromat. Mom wrote, “Old timers in the laundromat said it was unusual to get heavy rains.”

Rain called for a change in our travel plans. We arrived at Four Corners about 7:45 am.

It wasn’t the first-time rain would change my plans. The next time I (not my mom) had to keep the rain out. Instead of sleeping bags getting wet, my perspective was altered. That changed my life.

Four Corners is a cartographer’s version of Twister (we got the game for Christmas in 1967). We played.

One by one, we took turns and did down dog with one foot in Arizona, one in New Mexico, a hand in Utah and the other in Colorado. Then we reversed it putting a foot in Utah, one in Colorado, a hand in Arizona and the other hand in New Mexico. Then we tried this: one person does plank pointing north and the other does down dog pointing south … [laughter] we’re playing twister. The game came to and end in mountain pose. Mom stood in Utah, one of my sisters stood in New Mexico, the other sister in Colorado.

That left me in Arizona.

The University of Arizona, February 17, 2022.

Today, I am zoom speaking on my book The House of My Sojourn: Rhetoric, Women, and the Question of Authority to Dr. Cristia Ramírez’s graduate seminar at the University of Arizona. Her Contemporary Theories and Histories of Rhetoric has been assigned to read it.

Dr. Cristina Devereaux Ramírez is an Associate Professor and Program Director for the Rhetoric, Composition, and the Teaching of English (RCTE) graduate program in the Department of English at the University of Arizona. She received her doctoral degree in English with a focus in Rhetoric and Writing Studies at The University of Texas at El Paso in 2010

When Cristina invited me to speak, she sent this email. “I would love it if you could ZOOM in for one hour to come and talk to my students (2nd years) about your work and how you came to use the metaphor of building/architecture in your work. I think your work does an excellent job in framing the importance and still an absence of women in our discipline.”

Rhetoric is a theory. Which makes it very abstract. What made it ultimately so concrete and real to me –well I blame that on the rain.

I told the class about my experience of diving into a building to get out of the rain. It just so happened to be the U. S. Capitol.

The year was 1983. I was a graduate student and I had come to DC present my paper, listed in the program of the national convention as one of three top graduate-student papers.

Washington, D.C., 1983… I was so full of myself, heady with hope, and riding the winds of change. I was a Big Chick Graduate Student. I had the right to run. I had the right to pursue a professional career. My faith in human rights was being reaffirmed from Mexico to Nairobi.

The world to me in 1983 made me think I was on the edge of a future I had once only dreamed of. Now I had run a marathon and the United Nations a new decade for women.

A. Running a Marathon

I ran a marathon in 1981. It was The Daily Sentinel Mesa Monument Marathon 1981, Grand Junction, Colorado.

In less than a year I would be able to watch the first Women's Marathon at the Summer Olympics in Los Angeles in 1984.

Did you know? Before 1972, women had been barred from marathons. That rule did not keep women from running, though. In 1966, Roberta (Bobbi) Gibb hid behind a bush at the start of the Boston Marathon, sneaking into the field and finishing the race in an unofficial time of 3:21:25. She was the first woman known to complete the arduous Boston course.

Bobbi Gibb

B. My faith in human rights.

The United Nations Decade for Women spanned the years 1975-1985 and “consisted of three international forums and conferences: in Mexico City in 1975 to inaugurate the Decade; in Copenhagen in 1980 to give a mid-decade report; in Nairobi in 1985 to formulate strategies and goals for the future. In addition to these international meetings, the Decade occasioned numerous regional meetings of United Nations agencies and organizations (i.e., the United Nations Economic and Social Council [UNESCO], the World Health Organization [WHO], ECLA, the Euro-

pean Economic Council [EEC]) and regional meetings of non-govern-

mental organizations (i.e., YWCA, World Council of Churches, National

Association of Women), all to consider the status of women and to make

recommendations for women. The Decade also occasioned a multitude of

documents from governments and from public and private agencies and

organizations, both national and international.” (See Judith P. Zinsser, "From Mexico to Copenhagen to Nairobi: The United Nations Decade for Women, 1975-1985," Journal of World History 13, no. 1 (2002): 139-68.

What you need to know about me is that I ran a marathon because I had the right to run. What you need to know also is that I thought women were entering the realm of political participation and the whole world championed the rise of women. My beliefs about the world and what I knew I could do and was capable of however was stunned because of what I felt and saw that day in the Capitol. It was like the sleeping bag blanketing my soul got wet and there was no sun to dry it and no dryer anywhere. I had to do something.

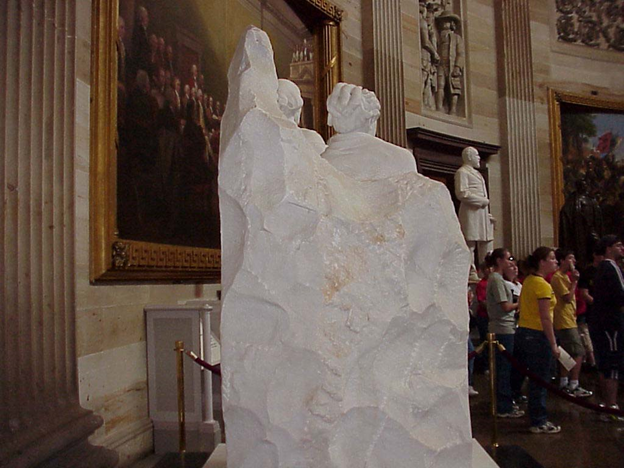

It was raining that November day in Washington, DC. I was near the Capitol and decided to stay dry. I walked up the stairs with the intent of seeing The Portrait Monument to Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Susan B. Anthony in the Capitol. I had read about the statue in one of old textbooks from the 1960s.

It had to be here somewhere. Where in the heck is it? It is a 14,000-pound sculpture! Why can’t I see it?*

*In 1997, the Portrait Monument was moved to the Rotunda. These pictures were taken in 2010.

The Portrait Monument was not in the Rotunda. It was in the basement of the U.S. Capitol. The statue was presented by the National Women’s Party to the people of the United States on February 10, 1921. But the Joint Committee on the Library authorized the installation in the basement. It sat near buckets and brooms. In 1963, the basement was remodeled; the Monument became available for public view in what was now called the Crypt. Three women, who had been engaged in the great debates that shaped our nation, were naught. The other 1000s of women --- Poof!

Why was Lucretia Mott in the Crypt? “Excusez-moi: : I thought the time was “Decade of Women.” You need to know that back at the convention I was hearing about women in rhetoric and disciplines related to the humanities. I had read journal articles nearly a decade old on Frances Wright published in the Quarterly Journal of Speech. Even 8 years ago, Ms. got in on the action publishing scholarship on women rhetoricians. The April 1976 issue had an article on Frances Wright: Celia Morris, "Frances Wright: She Fought the Major Battles of Her Time and Ours, 15-18+.

The House of My Sojourn is an exploration of rhetoric as a space. This metaphor enabled me to understand how and why women are excluded from the people’s art and the people’s hall. I concluded that we can’t break a glass ceiling. We must scrap the roof. Get out of old patterns and old ways of doing things.

Earlier I noted that rhetoric is a theory. Which makes it very abstract. What made it seem so concrete and real to me was the feeling of being in the U.S. Capitol back in 1983.

I started to see the U.S. Capitol as a space of rhetoric. It was a container that held the people who were engaged in the process of building a house of democracy.

Architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe labeled the Capitol’s rotunda “the Hall of the People.” It is where Freedom speaks. Aren’t women people?

Rhetoric is a house is a metaphor that shifted my attention to space rather than time. (Rhetoric is quintessentially an art of time. Think of Dr. Martin Luther King saying “ Now is the time to make real … Now is the time to rise from …. Now is the time to lift our …. Now is the time to make justice ….” in I Have a Dream.

More than 2500 years ago, Plato’s Gorgias cited rhetoric as the power that throws up the great walls and docks of Athens. The assertion here is that rhetoric makes architecture. Architecture makes civilization. Rhetoric is civilization.

The ancient Greeks worked on rhetoric because they believed in it. The art gave everyone a share in the city to distribute justice in order that there might be a city where the bonds of people relied on their inclusion and participation.

The Decade of Women has come and gone; the Year of the Woman (1992) as come and gone … When, if not now, is it time to design rhetoric for the present. As a power, what aspects of human motion, the flow of ideas, and their equal exchange can rhetoric throw up for us as it once threw up the walls and docks of Athens. It would be incredible to figure that out. Because rhetoric is not an actual building, but it pretends to be so, as the Capitol pretends to be a rhetoric—a hall of the people and the speech of freedom.

To the graduate students at Arizona, I tell them, I could no longer see rhetoric the same way.

Dr. Cristia Ramírez says, “it’s so important to see a woman voicing these concepts.”

There is more to come. More about light and darkness. About the glass ceiling and why breaking it isn’t enough. More about the ground beneath our feet.